HOW TO REDUCE THE risks OF PESTICIDE EXPOSURE for pollinators

The photo shows bumble bees feeding on flowers. Bumble bees and other pollinators can be harmed by pesticides applied to plants.

What are pollinators?

- Pollinators include honey bees, native bees, butterflies, and even hummingbirds. They all are attracted to plants’ flowers. Flowers provide food resources for pollinators, including nectar for energy and pollen for nutrients.

- As pollinators visit each flower, they collect pollen on their body. Then they transfer the pollen to the next flower. This transfer of pollen leads to sexual reproduction in plants to form fruits or seeds.

What are pesticides?

Pesticides are products designed to kill rodents, weeds, mosses, insects, plant diseases, slugs, and snails. Many of these products can directly and indirectly harm pollinators.

Planting Plans to Support Pollinators

See Enhancing Urban and Suburban Landscapes to Protect Pollinators (OSU Extension Service) for planting plans to support pollinator health in landscapes.

JUMP TO

- Understand Scenarios Where Pest Control Intersects with Beneficial Insects, Including Pollinators

- Understand Routes of Pesticide Exposure for Pollinators

- Use Bee-Friendly Pesticide Application Methods

- For Pest- & Disease-Prone Plants, Learn How to Protect Pollinators

FOR QUESTIONS ABOUT PESTICIDES

The National Pesticide Information Center (NPIC) can answer questions about pest control chemicals.

1-800-858-7378 or npic@ace.orst.edu

Overview

- Insecticides and miticides are used to control insects and mites on plants. They may directly harm pollinators such as bees and butterflies.

- Fungicides are used to treat plant disease such as leaf spot, rust, and powdery mildew. They don’t harm pollinators directly the way insecticides do. However, research shows that honey bees exposed to certain fungicides are more susceptible to parasites and diseases.

- Herbicides (weed killers) are used to control weeds. They can harm pollinators indirectly by damaging pollinators’ food sources: flowers.

- Using pesticides around pollinators in a manner that reduces exposure can be complicated.

Keys for Success

- Consider hiring a professional if you determine you need to use pesticide in your landscape. Licensed pesticide applicators have training to minimize risks to pollinators.

- If you choose to do it yourself, use information provided on pesticide labels to understand the risks of a product and how to apply it.

- Manage bee-attractive weeds before or after they flower. Avoid spraying flowers and pollinators directly.

- Look for information about hazards to pollinators in the ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS section of the pesticide label.

- Follow the instructions to minimize risks and maximize benefits.

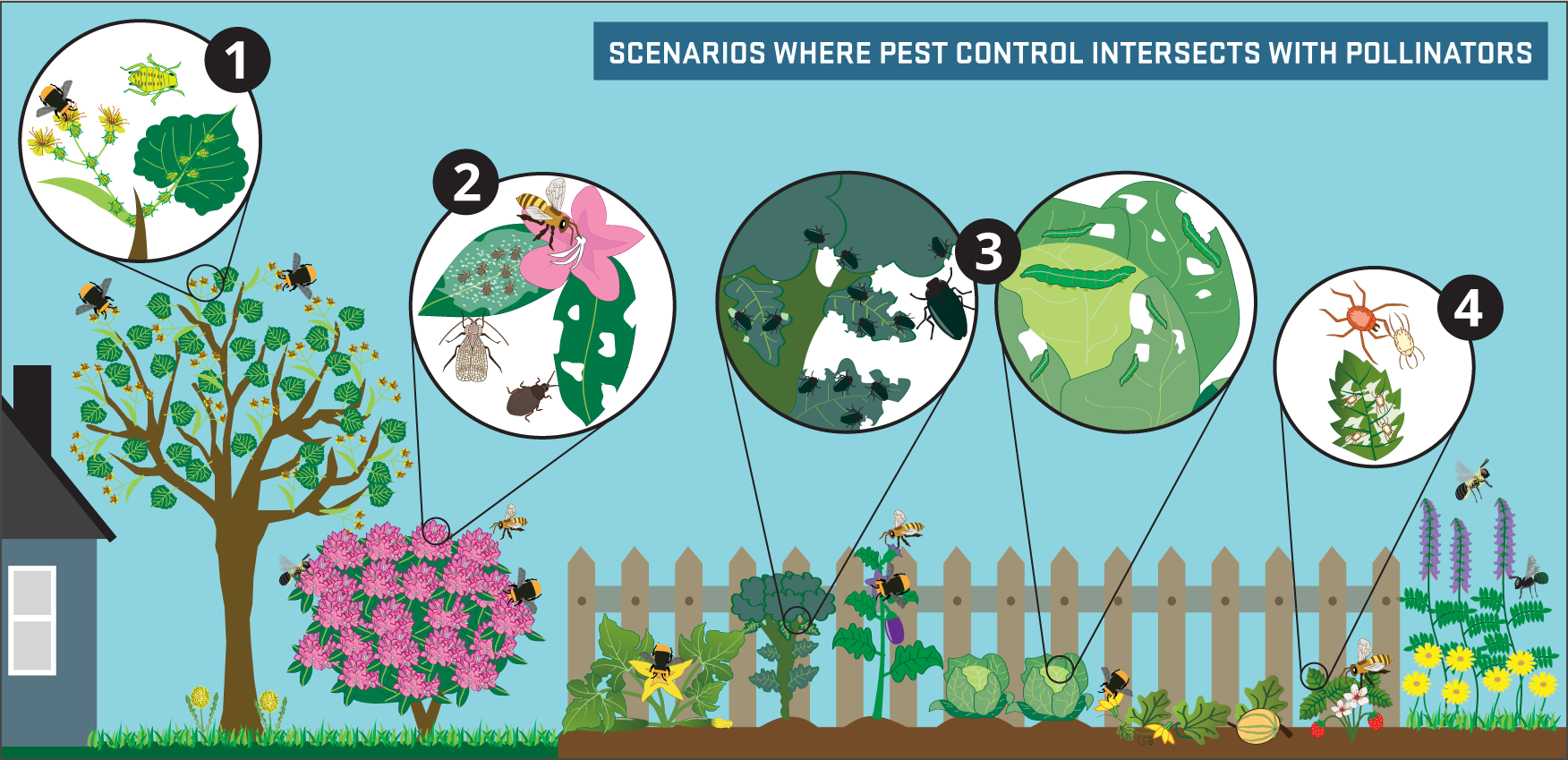

- Aphids on linden trees in flower

- Azalea lace bug and root weevil on rhododendrons in flower

- Flea beetles and cabbage worms on vegetables in the vicinity of flowers attractive to bees

- Spider mites and their natural enemies on flowering plants

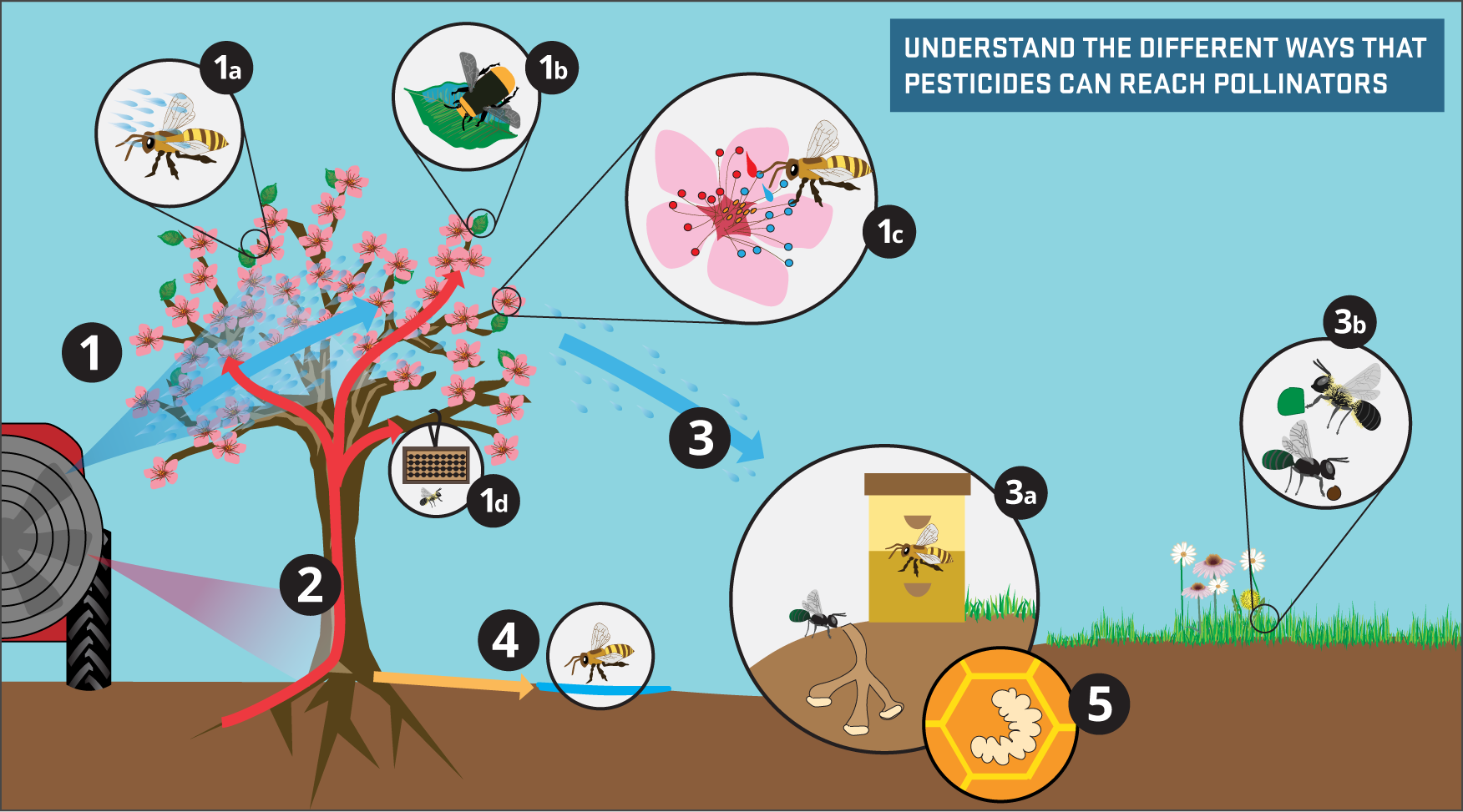

- (a) Exposure if sprayed directly, (b) contact with pesticides or pesticide residues that remain active on foliage and flowers, (c) ingestion of pesticides (both sprayed on plant and systemic) in pollen and nectar, and (d) direct exposure to mason bee nests

- In nectar and pollen for systemic pesticide treatments that are drawn up through a plant’s vascular system and appear in the nectar and pollen of flowers and leaves

- (a) Pesticide drift into areas where bees are foraging and (b) Drift into nesting or gathering nesting materials

- Pesticide runoff that contaminates water that bees forage on or the nesting beds of ground-nesting bees

- Pesticide drift and contaminated areas that can affect larvae through contaminated nectar, pollen, and cell material

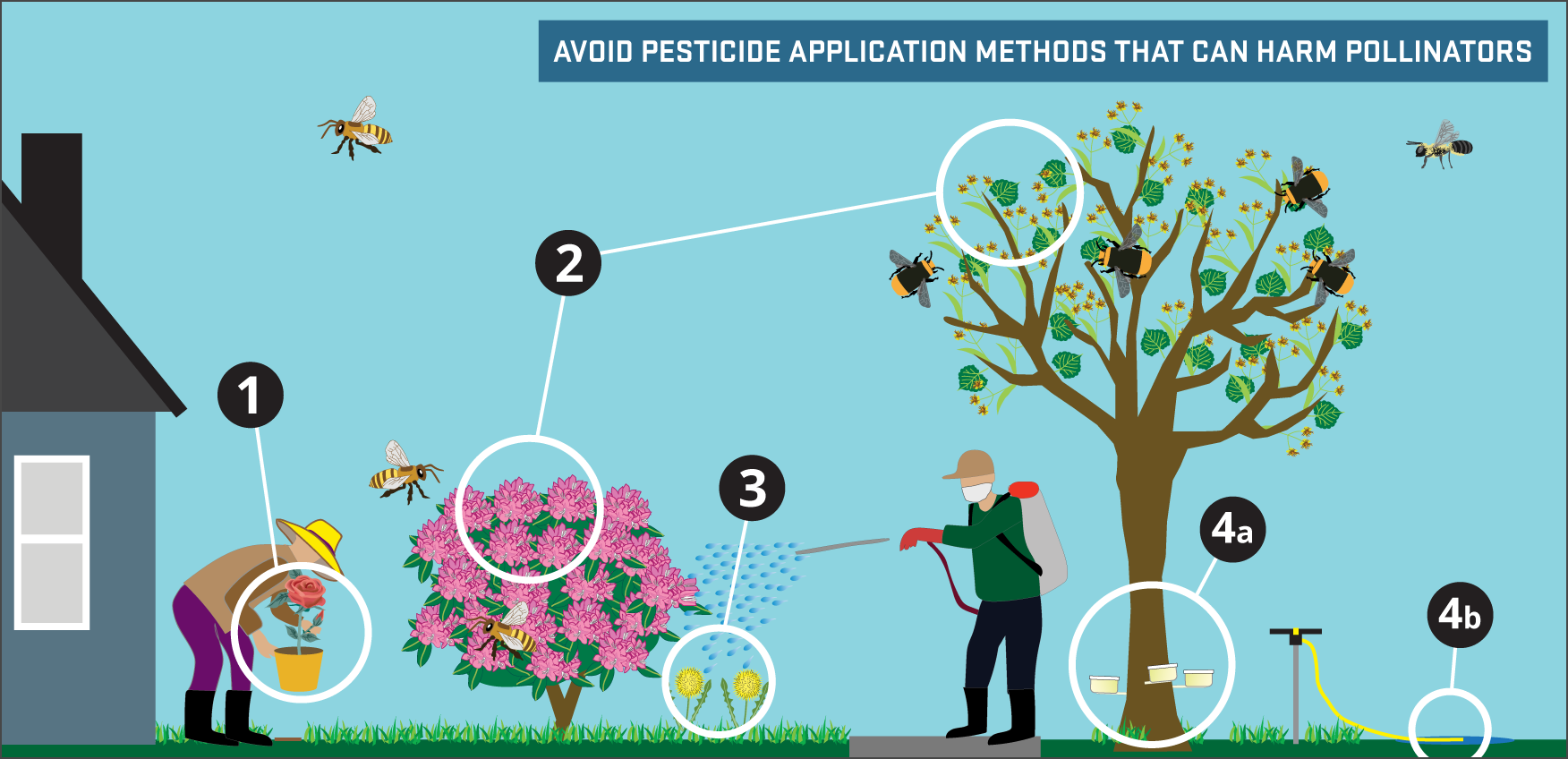

- AVOID pest-prone plants (see details below).

- DON’T spray plants during bloom.

- DON’T let spray drift onto blooming weeds.

- DON’T use (a) tree trunk injections or (b) soil drenches (neonicotinoids).

More methods To Reduce Pesticide Risks To Pollinators

- Don’t spray flowers directly, whether they are weeds, vegetables, or garden flowers.

- Always follow the label directions when applying a pesticide product. Pay special attention to the ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS section of the label.

- Don’t use products during bloom that are listed as “toxic to bees.”

- Check the weather. Don’t spray when it’s raining or when rain is expected in the next 24 hours. Don’t apply bee-toxic pesticides when dew is forecast. Dew may re-wet the pesticide and increase bee exposure.

- Choose the least hazardous formulation of a pesticide. Pesticide dusts are the most hazardous type of pesticide because they might stick to bee hairs the way pollen does. Granular formulations are the least hazardous when bees are present.

- The plants detailed below are both very attractive to pollinators AND prone to pest and disease problems that may invite the use of pesticides.

- The best way to protect pollinators is to select plants that are not prone to diseases and pests in the first place.

- Keep in mind that problems on landscape plants are strictly cosmetic. Controlling the problems is optional.

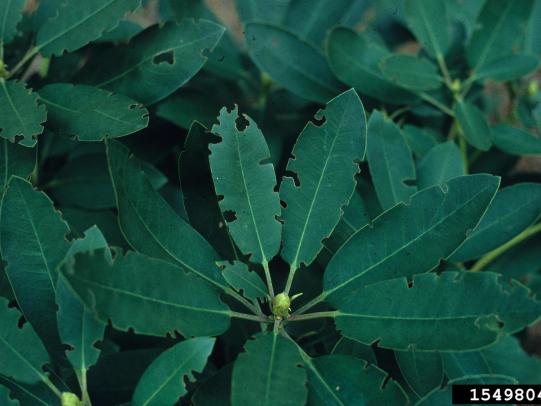

Tilia (Linden, Basswood) Aphids & thrips

- Tilia trees are highly prone to feeding damage from aphids and thrips. Tilia flowers are also attractive to pollinating insects such as honey bees and bumble bees.

- The feeding from aphids and thrips leads to a mess. A sticky substance (honeydew) and cast skins fall to the ground. Black sooty mold grows on the honeydew.

Recommendations for established Tilia trees near hard surfaces

- Encourage or release natural enemies of aphids. Beneficial insects include lady beetles, syrphid fly larvae, green lacewings, and parasitoid wasps.

- Wash honeydew from plants with a strong stream of water. Choose a time when leaves will dry quickly.

- Avoid excessive nitrogen fertilizer and overwatering. These practices make plants more attractive to aphids and other pests.

Recommendations for new Tilia plantings

- Plant a cultivar that is resistant to aphids, such as silver linden (Tilia tomentosa) and also T. platyphyllos and T. × euchlora.

- Plant a different type of tree altogether.

- If you must plant Tilia, don’t plant it near sidewalks, patios, car parks, or sitting areas. Only plant in spacious vegetated areas where sticky honeydew won’t be a problem.

It is illegal in Oregon to apply certain neonicotinoid insecticides on linden trees, basswood trees, or other Tilia species.

See Oregon Department of Agriculture’s 2015 PESTICIDE ADVISORY Bees and Linden Trees (PDF).

Neonicotinoids include active ingredients such as dinotefuran, clothianidin, imidacloprid, and thiamethoxam.

- These products are absorbed by one plant part (e.g., stems or roots) and move to leaves or other plant parts.

- Following application, the poison may be found in flowers for months or years.

- Beneficial insects feed on the nectar and pollen.

Tilia species’ flowers are very attractive to bees.

Apply this same reasoning to other bee-attractive shade trees and woody ornamental shrubs.

If you suspect a pesticide incident with bees, call the Oregon Department of Agriculture at

503-986-4635.

Apple & Crabapple Diseases & Insect pestS

Apple and crabapple flowers are highly attractive to pollinators. However, apples and crabapple flowers, fruit, leaves, and stems are susceptible to various diseases and pests, including:

- Apple scab

- Fire blight

- Codling moth

Pesticides (insecticides and fungicides) used to treat these problems can be harmful to pollinating insects. Avoid applying pesticides to apples and crabapple trees during flower bloom.

Manage apple & crabapple problems to minimize need for pesticides, particularly around bloom time

- For apple scab and fire blight, use resistant apple cultivars to minimize the disease impact. See Apple Cultivar Susceptibility (Scab, Fire Blight, Powdery Mildew, and Bitter Pit) (PNW Plant Disease Management Handbook).

- For apple scab, time fungicide sprays for before and after flower-blooming period.

- For codling moth, use non-chemical control methods such as: clean up fallen fruit, bag fruit to exclude codling moth larvae, and use of pheromone traps.

- If you determine an insecticide is necessary to control codling moth, time sprays before and after the flower-blooming period.

Azalea lace bug

Azalea lace bug (Stephanitis pyrioides) is a new pest to the Pacific Northwest. It causes leaf damage to azaleas and rhododendrons.

- Lace bugs have piercing/sucking mouth parts.

- The initial damage shows up as light-yellow stippling on the surface of leaves.

- Higher populations can cause more severe damage on azaleas, causing the leaves to turn nearly white.

- On rhododendrons, severe damage may look like iron chlorosis with yellow leaves and green veins.

Manage azalea lace bugs to minimize the need for insecticides, particularly around bloom time.

- Choose new plants from resistant cultivars or grow plants other than rhododendrons and azaleas.

- Healthy, non-stressed plants are more resistant than stressed plants.

- Encourage natural enemies such as lady beetles and lacewings.

- Monitor for hatching of nymphs (late May-June) and wash the underside of all leaves with a strong jet of water to remove them. This step, plus lacewing predation, can effectively control lace bugs.

- Least-toxic sprays can be effective if applied with complete coverage. Don’t apply when plants are in bloom and pollinators are present. Insecticidal soap and neem are least-toxic insecticide options.

- Avoid neonicotinoid pesticide products. These systemic insecticides can make their way to flowers and harm pollinating insects.

Azalea bark scale

Bark scale (Eriococcus azaleae) is a common pest of rhododendrons and azaleas, as well as several other common ornamental plants, including hawthorn, andromeda (Pieris), and even blueberries.

Manage scale insects to minimize need for pesticides, particularly around bloom time

- Inspect plants before introducing them into your garden, to make sure they are not infested with scale.

- Discourage ants that may be present, because they defend the scale from natural enemies, and may move them to other plants.

- Encourage natural enemies such as ladybugs and lacewings.

- Avoid excessive nitrogen fertilizer; it will make the plants more attractive to scale and other pests.

Rhododendron Black Vine weevils

Black vine weevils (Otiorhynchus sulcatus) cause both leaf and root damage to susceptible cultivars of rhododendron. They also damage many other plants, including strawberries and hops. The soil-borne larvae eat the roots and weaken the overall health of plants.

Manage black vine weevil to minimize the need for insecticides, particularly around bloom time

- For established plantings, promote good plant health by providing water, mulch, and fertilizer. Healthy plants are more resistant to pest outbreaks.

- For new plantings, seek out cultivars that are resistant to root weevils. For example, the rhododendron variety ‘P.J.M.’ is strongly resistant to root weevils. It suffers very little damage from root weevils.

- Beneficial nematodes kill the soil-dwelling larvae stage of root weevils. These products are best applied in the late summer or early fall when soil temperatures are warm.

Roses problems (Single-flowering)

Rugosa roses (Rosa rugosa) and native roses (R. nutkana and R. woodsii) have single flowers that are highly attractive to pollinators. Fortunately, these roses are not as prone to the major pests and diseases that attack many ornamental rose varieties. Roses with showy (double) flowers aren’t as attractive to pollinators as single-flowering varieties.

However, being rose family plants, single-flowering roses are still susceptible to problems:

- Aphids and thrips that feed on leaves, stems, and flowers

- Diseases such as black spot, rust, and powdery mildew that attack rose leaves, stems, and flowers

- Insecticide and fungicide sprays for roses can be harmful to pollinating insects and should not be applied during bloom time.

- Choose to plant varieties known to be resistant to black spot, rose rust, and powdery mildew. See Rose Cultivar Resistance (PNW Plant Disease Management Handbook). Miniature roses typically are more susceptible than other types.

- Grow roses in full sun and avoid overhead watering.

- Keep roses pruned to maximize air flow and drying of leaves.

- Go easy on the nitrogen fertilizer, which promotes lush growth that can attract aphids.

- Scout plants weekly, and squash aphids as they appear.

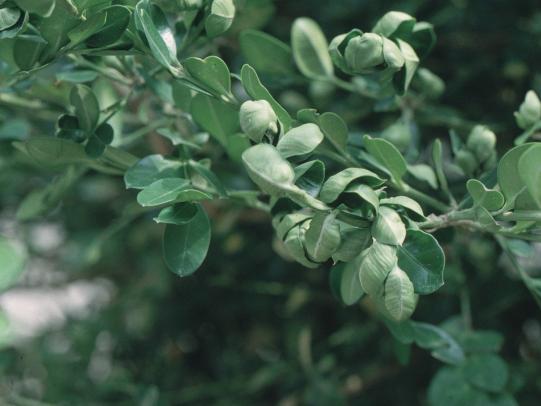

Boxwood Leaf Miners & Psyllids

Boxwood produces small, yellowish-green flowers that attract pollinators.

Boxwood is also prone to insect problems:

- Leaf miners

- Psyllids

Manage to minimize the need for insecticides, particularly around bloom time

- For leaf miner, the larvae are protected inside the leaf layers. Insecticide sprays are not effective to control it. Tolerate the damage.

- Plant psyllid-resistant cultivars. Of the common box species, Buxus sempervirens (English boxwood) is somewhat less prone to psyllid than the other species. B. microphylla (littleleaf boxwood), and B. sinica var. insularis (Korean littleleaf boxwood) are more prone.

- Pick off infested leaves (leaf miner) or clip out infested branches (psyllid).

Content provided by writer Signe Danler and editor Weston Miller. Content reviewed by Andony Melathopoulos.

PESTICIDES & POLLINATORS REFERENCES

How to Reduce Bee Poisoning from Pesticides

PNW Insect Management Handbook

Bee and Pollinator Health Publications

Oregon State University

Resources for Pesticide Applicators

Oregon Bee Project

Resources for Landscapers

Oregon Bee Project

Resources for Gardeners

Oregon Bee Project

Pollinator Conservation Resources: Pacific Northwest Region

Xerces Society

Recursos en Español

Oregon Bee Project